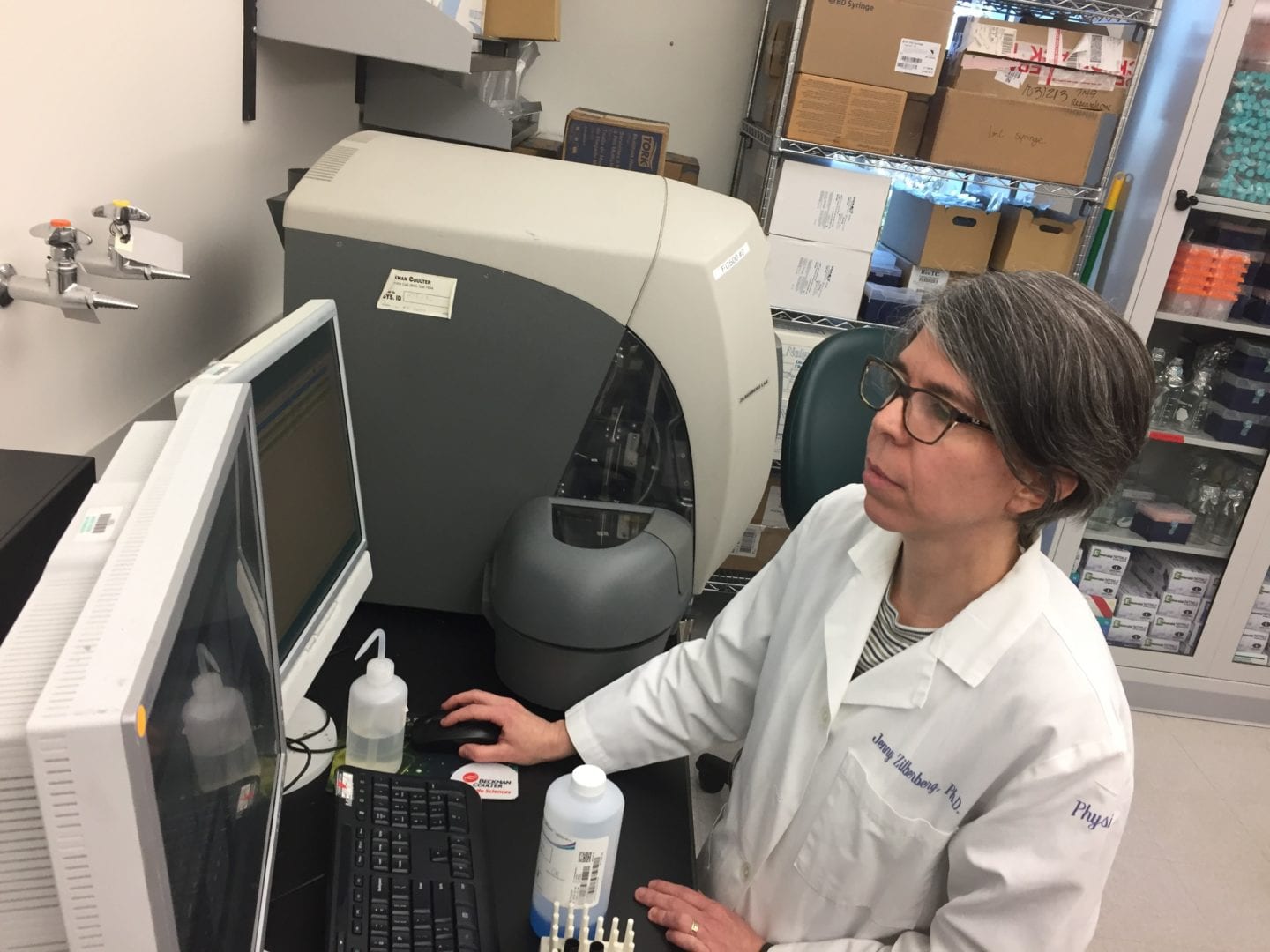

The CDI Experts: Zilberberg and Her Lab Build Models for Breakthroughs

July 31, 2020

The culture platform, hosted in a CO2 incubator, is programmed to rock back and forth, on and on for days. Cells inside are subjected to shear forces due to the slight variations in hydrostatic pressure through the movement. The rocking motion is a clever way to mimic important stimulatory forces on cells occurring naturally inside the human body. This method may just hold the key to maintaining viable cancer cells outside of a patient’s body – allowing more research than ever to be done on some deadly tumors.

The scientist engineering these novel platforms is Jenny Zilberberg, Ph.D., an associate member of the Hackensack Meridian Center for Discovery and Innovation (CDI), who began her career as a chemical engineer. Her training, plus thousands of hours in the lab, have resulted in the development of ex vivo (outside the body) biomimetic cancer models – particularly on the environment within the human bone, the home of multiple myeloma and other cancers that metastasize to this site. The models, designed to be high throughput, offer an opportunity for huge amounts of research at a faster clip than could be conducted in mouse, in vivo (inside the body) models, or even other in-vitro culture systems.

Importantly, because it uses a small amount of the patient’s own tumor cells, the experiments are furthermore cost effective – and results are likely to be more translatable than those obtained using animal models.

The developed models are a matter of reducing the variables down to their barest essentials, in order to sufficiently mimic the in vivo tumor microenvironment.

“Simplicity, for me, is the essence,” said Zilberberg, who says she wants to make sure that others can also take advantage of these systems.

“Dr. Zilberberg’s expertise in creating models is an important part of the chain of the discovery in the work we do,” said David S. Perlin, Ph.D., chief scientific officer and senior vice president of the CDI.

“Jenny Zilberberg and her models are helping us advance the science undergirding oncology treatments of the future,” said David S. Siegel, M.D., Ph.D., chief of the Multiple Myeloma Division at John Theurer Cancer Center, founding director of the Institute for Multiple Myeloma and Lymphoma at the CDI, and also a collaborator of this research endeavor.

SMALL MODELS, BIG RESULTS

Multiple myeloma is a cancer which has proven among the toughest medical riddles. One of its biggest challenges: having representative research models to test a wide variety of potential treatment options and better understand what is going at the molecular level.

Using her expertise in engineering, immunology, and cancer, Zilberberg has created a model which mimics the environment of the bone marrow where multiple myeloma takes root. Her models and culture methods recapitulate “key elements” of the disease niche, such that patient cells can be preserved – while remaining simple enough to tease out important mechanism underlaying myeloma’s development of drug resistance.

The challenge is harder than it may initially appear to a layperson. The environment is a surprisingly dynamic place. Fluid-induced pressure within the bone and marrow means there is a specific recipe for creating this natural environment outside the body.

The breakthrough for Zilberberg and her collaborators at the Stevens Institute of Technology is two-fold: first, the successful ex vivo preservation of multiple myeloma cells from patients for more than 3 weeks; and secondly, the culturing of primary mouse and human osteocytes capable of producing sclerostin and FGF23: two crucial markers produced by osteocytes in vivo.

In short, the ex vivo model by Zilberberg and team have put together is a microcosm of what’s going on with cancer in its home in the human body.

These “biomimetic platforms” are defined as “the imitation of the models, systems, and elements of nature for the purpose of solving complex human problems.” The models are currently undergoing further refinement and validation in the final year of a two-stage, five-year National Cancer Institute grant for the work.

Dr. Zilberberg and her collaborators are using these platforms to identify biomarkers associated with drug resistance and potential mechanism of immune suppression elicited by the tumor microenvironment. Crucially, because patient-derived myeloma cancer cells can be maintained ex vivo through her culture methods, the platforms can potentially be used for personalized screening and treatment selection. Dr. Zilberberg and her team have also explored the interactions of metastatic prostate cancer cells with the bone in these models. The platform is now also being modified to test cellular immunotherapies, which are broadening the treatment options for a number of cancer patients.

VENEZUELA, TO AMERICA.

Her love of science started early, in her native Venezuela. Her father was a geologist, and his teachings helped cultivate her curiosity in both the natural world, and the way things work.

Originally, she studied chemical engineering, earning her undergraduate degree from the Universidad Simón Bolívar. But after a short stint with the oil industry in that country, she realized she wanted to do “anything but work in the field.”

While still in Venezuela, she conducted a thesis project on the flow and viscosity of blood in certain heart disease patients. That touched off a whole new path, which eventually led to graduate degrees in bioengineering, culminating in her Ph.D.

After postdoctoral experiences at the University of Pennsylvania and Thomas Jefferson University, she came to what eventually became Hackensack Meridian Health in 2005.

Along the way, she and her husband had three children, now ages 13, 11, and 8.

“They’re the three best experiments I’ve ever done,” she said recently, in her office on the fourth floor of CDI.

NEXT UP… THE GUT.

The human gut – the incredibly complex milieu that makes up part of our digestive tract – is the next model target for Zilberberg. She is seeking funding opportunities to continue building models for the complex environment of the microbiome there.

The culture platforms already developed in her lab are the starting point of this new project, which also incorporated her training in immunology and gut inflammation.

“My job is a lot of invention – and not just discovery,” she said.